Season 2: Episode 1

You are listening to the Shortcut to Slim Podcast. Show details — Hosted by Lindsay S Nixon — Season 2: Episode 1;

Transcript

If you’ve ever felt like diet is basically DIE with a T on the end…

Or have been miserably hungry while trying to lose weight…

Or started having obsessive food thoughts…

This episode will explain WHY and what you can do about it.

Plus I’ll dig into the physical and psychological differences between fasting and caloric restriction… which also means you’re going to learn about gherlin and ketosis!

After last season I swore up and down I wouldn’t talk anymore on fasting because I’d exhausted that topic and wanted to focus on the brain.

And I was committed.

I went face down into stacks of research on neuroscience and uncovered some seriously cool studies on food psychology and became totally obsessed CBT (cognitive behavior therapy) is my favorite…

but then right at the end my work whipped right back around to fasting so here we are again.

But you know, that’s cool. I like a bridge.

I like that the research from Season 1 fits connects with season 2.

So here we are.

Last season I cracked open the myth about starvation mode.

It doesn’t exist.

There’s not a scrap of evidence to support the idea that you’re not losing weight because you’re not eating enough.

Now if you go a long time eating *severely* reduced calories your metabolism may slow down a bit, but it doesn’t slow enough to stop weight-loss completely, and even if you did slow it down, it’s still not “Game over” because you can’t “break your metabolism.”

You also can’d “fan the metabolic flames” and make your metabolism ‘faster’ by eating small meals or snacks. (That is still the worst diet advice ever… If you need a refresher, listen to season 1, episode 3).

But while “starvation mode” doesn’t exist, starvation does.

(And by starvation I mean FAMINE, which fortunately, no one reading this is at risk for.)

HOWEVER,

- if you eat well below your caloric needs for a long time AND

- you’ve coupled that with exercise OR

- you’re otherwise suffering mentally (and many of us feel diets are DIE with a ‘T’ on the end—that’s suffering)

You may experience extreme hunger, making “starvation” FEEL incredibly real and THAT can be a problem psychologically and physically.

THE RESEARCH

When I poked holes in the myth around starvation mode last season, I referenced the Minnesota Starvation Experiment from the 1940’s.

The main goal of that study was to get the men to lose about 2.5 pounds a week, which is pretty aggressive weight-loss for someone who is already at a healthy weight with little body fat to lose as the men were.

To accomplish this, the men were given less than half of the calories they needed to survive and they were required to walk 22 miles a week. Intense stuff.

Their diet was almost primarily carbohydrate based: breads, pasta, tubers. Little to no dairy or meat since the researchers were trying to mimic the diet of people in starving, war torn areas.

If starving them to extreme thinness was the goal, the study was a success.

The pictures of the men at the end of the study are really hard to look at.

But they did lose weight.

Source: mnopedia

Source: Mad Science Museum

They also lost a lot of muscle mass, which makes sense.

When your body starts starving and it can’t tap into stores of body fat, it will cannibalize muscle as a survival measure.

The men also reported psychological changes like obsessive food thoughts.

This reminded me of the Robertson family, who I talked about in Season 1.

If you don’t remember them, the Robertson family survived out on the ocean for 38 days. It’s the longest ocean survival we know of, and although they caught and ate more than enough fish and turtles to eat (raw), they were plagued with constant and intense hunger.

War hero Louis Zamperini, who was also at sea for a long time, but without much food, also had obsessive food thoughts. Zamperini said fantasized about food more than he fantasized about rescue.

Let’s compare all this to the case of Angus Barbieri

who fasted for the year of 1965.

That’s right, Barbieri went some 380 days without any food.

He started at 456 pounds and lost a total of 276 pounds by the end.

Image Source: Science Alert

Barbieri felt good, was healthy according to his doctor, and he didn’t experience obsessive food thoughts.

He didn’t even experience much hunger, which I’ll get to in a minute.

There’s also the more recent Andrew Taylor, who only ate potatoes in 2016.

Image Source: Today Show

Taylor started at 335 pounds and lost over 100 pounds.

Unlike Barbieri, Taylor was eating something, but his diet was strikingly similar to those Minnesota men.

Taylor also said felt good, had improved blood work and reported no obsessive food thoughts.

In fact, when reporters asked Taylor about what he was most excited to eat again, he struggled to answer, saying he was happy just to eat more potatoes.

I’ve also had friends and colleagues who water fasted for a few days, some for several weeks.

Two do it for health reasons.

One as a protocol for cancer treatment (Research shows that fasting slows or stops rapidly dividing cells and triggers energetic crisis that makes cancers cells selectively vulnerable to chemo and radiation)

The other for treatment of Lyme disease.

A few others do it for spiritual reasons.

I asked them about their experiences and dove into fasting forums.

It turns out that lots of people fast, for all different reasons, but whatever the reason, the general consensus is:

everyone experiences some hunger and irritation early on, but hunger all-out vanishes after a few days and then they’re fine.

A lot of people don’t end their fast until their hunger returns, which is usually around 10 to 14 days.

From an evolutionary “survival” standpoint, this makes perfect sense.

Initially, when you go without food your body is like:

Hey you! You forgot! We need to eat. Here’s a hunger signal to remind you.

It’s like your car turning the “low gas” light on.

But then you still don’t eat, so the body, like a petulant child, ramps up the signal…

My car’s gas light goes from an orange to red when I go from a quarter tank to about one-eighth a tank.

In the body, our hunger intensifies in the same way and our thoughts drift to food....

Now, up until the almost-out moment, our body was operating as usual. There was no cause for concern.

How many times have you left work with less than a quarter tank of gas, but weren’t worried about it because you’ve made the drive 20 times before. You knew you could make it home, but… oh crap.

There’s unexpected traffic and shiitake, the gas station you normally could stop at is CLOSED too.

A little bit of panic sets in.

You turn off the AC and roll down the windows hoping to save gas.

Maybe you also keep your foot of the petal and try to coast down the hill.

Your body does this too.

That’s when you start feeling brain fog or lethargic.

Here’s where your body and car start to differ: Eventually your car actually runs out of gas. You’re stranded and have to call AAA.

Your body runs out too, but luckily, your body has a spare gas can in your trunk! (Yes that was both literal and metaphorical LOL)

Your body starts using your fat (this process is called ketosis and I’ll come back to it in a minute).

When you go into ketosis, which takes about 3 days, your hunger drive is suppressed.

Why? You need to find food to survive.

You body knows this.

It also knows you’re not going to do that sitting in the cave feeling hungry, weak, miserable, and sorry for yourself!

Hunger is suppressed as a protective measure so you can feel good again so you get up go out, and find some damn food.

This perfectly explains why fasters stop feeling hunger after three days, and also helps explain why many fasters (and I’m included in this group) report enhanced mental clarity at this stage.

From a survival instinct this too makes sense. If you only have that 1 spare can of gas, you’ve got to get the most out of it to find replacement fuel as quickly as possible. You need to be laser focused… it’s GAME TIME!

AND since this is a science-based podcast and not an anecdotal one:

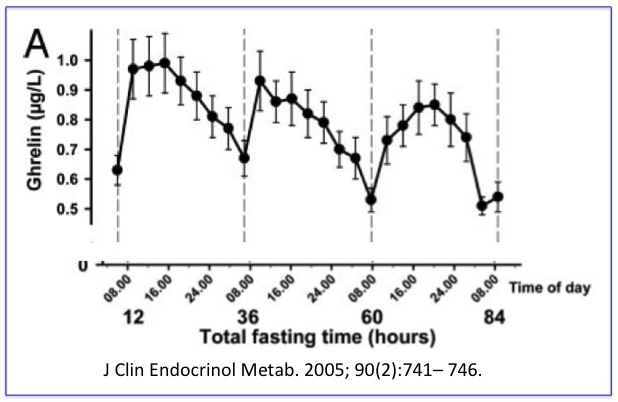

The levels of Grehlin in the blood of people fasting confirm all this.

Ghrelin is the "hunger hormone" that’s produced in the gastrointestinal tract.

It functions as a neuropeptide in the CNS (central nervous system), basically it’s a neuron text message.

Ghrelin regulates appetite and is secreted when the stomach is empty. This is like a text message to the brain, saying, “YO no food down here!” telling you that you are hungry.

Once the stomach is stretched with consumed food, secretion of Ghrelin stops.

This is one reason why “wait 15 minutes before getting seconds” is such good advice.

It gives your stomach and brain a chance to send and read texts.

If you remember leptin from last season (leptin is the satiety hormone), Gherlin is the direct opposite.

So what does gherlin have to do with the fasting experience?

The longer people fast, that is, the longer they go without food, the more their Ghrelin decreases. We see this clearly in the blood work of people fasting.

What I found particularly interesting looking at this blood work was how the body appears to be adapted to eating.

Specifically, in the first few days of fasting, the Ghrelin PEAKS at traditional meal times, even though the subjects were fasting.

The body was anticipating… prepared… stimulating their hunger like clockwork.

With each passing day these peaks in Ghrelin became smaller and smaller, but these results heavily suggest, if not conclusively prove, that you literally train yourself to be hungry at certain times through systematic eating.

This also confirms why 6 small meals a day or constant eating (including snacking) is such a bad idea, especially when you’re trying to lose weight.

It puts you completely out of touch with your hunger, stimulates false hunger, and the farther you are from true hunger *in general* the more you’ll overeat.

Sidebar: I haven’t found a lot of research on this yet, but I suspect bigger, but fewer meals, would mean less Gherlin.

One last note about the Gherlin peaks: they were peaks.

Hunger performs like a wave: It eventually breaks. This happens every time you feel hungry, whether you are on a long fast or not.

Most dieters fear their hunger will get so big it will get out of control and away from them. While hunger does peak, it also recedes and the top of the wave isn’t as high as you think.

You’ve already lived through this hunger-wave experience.

We’ve all had days at work where come lunchtime we were hungry. We felt hungry, even really REALLY hungry, but because our boss was yelling at us, or we were on a deadline, we worked through lunch. At some point we stop feeling the hunger, but we don’t notice it… it isn’t until hours later, usually when we start feeling droopy or it’s getting close to dinner, that we remember OOPS! I totally forgot to eat lunch today.

This happens to me a lot, not at work, but when I’m vacationing.

Walking is a natural appetite suppressant for me so if you stick me in a new city where I’m walking around and touring new stuff all day, I completely “forget” about eating.

I can’t do this at home where the kitchen calls my name, but I can just as easily do it at the mall.

In fact, the next time I decide to fast, I’m making it an errand day!

Now that you understand Gherlin, let’s talk super quickly about ketosis.

KETOSIS

Ketosis = fat burning mode.

If you don’t eat anything for a long time you’ll enter ketosis, which is when your body primarily uses keytones (derived from fat stored on your body or fats you ingest) for energy instead of glucose (blood sugar).

You can also enter ketosis by eating an extremely high amount of fat and a very low amount of carbohydrates (this is the purpose of why people do Atkins or it’s more modern sibling the ketogenic diet).

BUT it’s not an all-you-can-eat fat buffet.

The only way a ketogenic diet will work for fat loss is when there are fewer calories coming in than you need to maintain your weight because there is always that one, simple truth with dieting.

You can also get to this state with a 100% carbohydrate diet (meaning 0% fat) or what I like to call “potatasis” but that’s a hack for another time. (This is what Andrew Taylor, above, did).

But wait.

We got a little sidetracked.

What are the differences here?????

Why are there such dramatic, different physiological and psychological responses between the Minnesota men, Barberei, Taylor, the Robertson family, and these fun time fasters?

There are two theories or scientific camps on this.

#1 The first explanation is that the Minnesota Men were not fasting.

They were still eating. Drastically decreased calories, but it was still enough to keep them out of ketosis, which meant their hunger drive never quieted, and they were never able to use their body fat for energy. (This would also explain their muscle loss, without entering ketosis, gluconeogenesis would be necessary.)

Using my pantry example from last season, there was a lock around the pantry door that they couldn’t open. The help was there but not accessible.

#2 The other explanation is that light meals keep you ravenously hungry.

That eating “turns on hunger.”

This is definitely something I have experienced both with fasting long-term and through intermittent fasting. I might not be very hungry when I break my fast with food but as soon as I start eating, my hunger comes out to play in full force.

If I’m on an airplane and I feel hungry, I will put off eating as long as I can, usually until the light is over, before eating because I know my hunger wave will go away but if I give into it and eat I’ll wind up more miserable because I’ll plow through my snack, feel hungrier, and have no immediate access to food to solve that situation so I have to sit there and take it. No thanks.

I’ve had difficulty sciencing this.

Meaning plenty of “experts” make this argument and push this theory but it’s not one that is easily proved with blood work or data.

The cleanest justification or scientific backing I’ve got here is that hunger is hormonal and eating (or not eating) affects hormones and Gherlin is a hormone… so there.

I know, that was unsatisfactory but that’s metabolic endocrinology for you.

I also can’t overstate this: The Minnesota men were not fat to begin with. They had little fat to lose at the start. It is difficult to compare the forced starvation of a thin person in famine, to an overweight person not in famine but trying to reduce calories to burn the fat stores that were created for that very purpose.

That alone could explain why Taylor and Barberi had completely different experiences.

But there is still one more massive component that no one else is considering, and that’s the basis of this entire season, which is:

THE MENTAL SUFFERING COMPONENT

That was something I noticed when interviewing meal plan users who had tried intermittent fasting for episode 11.

People loved intermittent fasting or they hated it.

You can listen to episode 11 here.

When I was looking back over the details of the Minnesota experiment, I found it fascinating that initially the men were allowed to chew gum, until it was discovered that some of the participants were chewing 40 packs a day.

This jumped out at me because when I was interviewing Meal Mentor users who tried intermittent fasting, a whole lot of them who admitted to binging on gum, or diet soda, or packets of mustard or splenda.

I started to wonder what role mindset played

In terms of “I’m fasting to beat cancer yay” versus “I’m depriving myself, I hate dieting.”

Or how “rule followers” (like me) love things that are simple, clearly black and white. That reduces anxiety for us, where others rage against being told what to do. (I’ll really dig into this in a further episode).

Going back to the mental suffering component

I think this is an equally strong explanation for why there such dramatic, different physiological and psychological responses to fasting and caloric deprivation.

There is related research to support this theory.

Remember the pudding study from Season 1 when I talked about exercise?

The short story is that any time we suffer (and whether you’re willing to admit it or not, exercise is a form of suffering for most of us) we seek rewards, usually in the form of food, consciously and subconsciously.

Listen to season 1 episode 10 for more information here.

The differing mindset also helps explain why I do so incredibly well with fasting in any form and my husband doesn’t.

If I have more willpower or discipline than him, it’s not by much.

The difference is I’m always excited about a fast. I love a challenge! I’m also curious about the research and the results. I practically spin like a top ready to spit into tubes and test my blood sugar.

I just can’t wait to turn my toilet into a laboratory!

My husband does not share my enthusiasm and often drops out of my studies because he finds he gets too depressed. And he does, I‘ve seen it. He gets completely melancholy where as people start asking me if I’ve popped a percocet.

Interesting stuff and I can’t wait to dig into neuroscience, psychology, mindsets, and will power with you in Season 2.

For now, here’s what can you take away from this episode:

Fasting (eating nothing) is different than Caloric Restriction (eating less) and if you’re going to eat less, you probably don’t want to divide the food up. Light meals like snacking can keep you ravenously hungry.

And speaking of hunger, you can condition your body to be hungry, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but something you should be aware of.

Hunger is also a wave meaning it peaks but it also recedes and the motion of the hunger oceans gets less dramatic the longer you go without food.

At the bottom of this post I’ve included more commentary on the Minnesota Starvation study. Additional aspects to consider, such as what effect the specific diet had on the data. This is not in the audio recording.

Finally, what’s happening the rest of Season 2?

A lot of science and shortcuts. Hacks you can do to your environment and your psyche so you can succeed to slim without all the blood, sweat, and tears of willpower.

Discipline is great, but just being awesome without worrying about it is even better. Stay tuned.

Download your free research-based 7-day meal plan here.

Leave the guesswork and science to me.

Was this helpful? Please rate the show on itunes

=======================

MORE THOUGHTS - ADDENDUM

For the first three months, the men in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment ate over 3,000 calories per day, which is a lot. A very active man of the subjects size would only need about 2,600 calories.

This matters for two reasons:

1. The initial “overfeeding” likely stimulated the body to run hotter (to burn excess off as heat) and/or increased N.E.A.T. and/or caused the metabolism to run slightly faster when entering the study and/or caused pre-set waves of ghrelin… any or all of which would contribute to a more miserable experience and/or skew results.

2. The diet was nearly all carbohydrates, which means there was little fat so nearly any overages could not be stored before or during the study. They were literally “zero-ing out their pantry” and having nothing to rely on for a rainy day (and it rained 24/7).

The diet was mostly processed carbohydrates (bread and pasta).

This matters for three reasons:

1. The amount of processed carbohydrates (simple sugars) would have affected insulin and other hormones, which independently as well as together, would have affected their physical and psychological experience.

2. The lack of fiber would mean the men rarely felt satiated and without satiation there is no signal to the brain to stop sending hunger messages. This too affects hormones.

3. Heavily processed carbohydrates can make some people overeat and feel more hungry.

Then men were also required to walk approximately 3.14 miles per day (6,286 steps).

This matters for two reasons:

1. Exercise often increases one’s hunger drive.

2. Low-grade exercise (walking) can reduce, but will not fully deplete glycogen, keeping them in a perpetual state of “almost out of gas.” This state would absolutely make them feel awful, tired, and extremely hungry, especially since their diet (re-feedings) did little to repair the energetic criss. Moderate to intense exercise, however, fully depletes glycogen, which encourages ketosis in a fasted state.

I also can’t overstate this: These men were not fat to begin with. They had little fat to lose at the start. It is difficult to compare the forced starvation of a thin person in famine, to an overweight person not in famine but trying to reduce calories to burn the fat stores that were created for that very purpose. The are massive psychical and psychological differences there, reference back to Taylor and Barberi.

=======================

REFERENCES (SHOW NOTES):

- NCBI: Fasting unmasks a strong inverse association between ghrelin and cortisol in serum: studies in obese and normal-weight subjects.

- 'Spud Fit': Man loses 115 pounds eating nothing but potatoes for a year

- Starvation Experiment of Dr. Ancel Keys, 1944–1945

- Telegraph: Why Fasting is Now Back in fashion

- The Atlantic: One Month Without Food

- Six Day Water Fast

- What’s the difference between fasting and eating less?